Relationships live in this Dynamic Tension

Healthy egalitarian, interdependent relationships live in a dynamic tension between wanting our own way in pursuit of an authentic, self-actualized life, and yielding to others from other-centered love. Imbalance in either direction brings problems for oneself and for those with whom we are in relationship. The key is a balance of self-protection and protection of another. To say it another way, the ideal relationship is one of mutual giving, so that neither side feels they have to take from the other to achieve a self-actualized life.

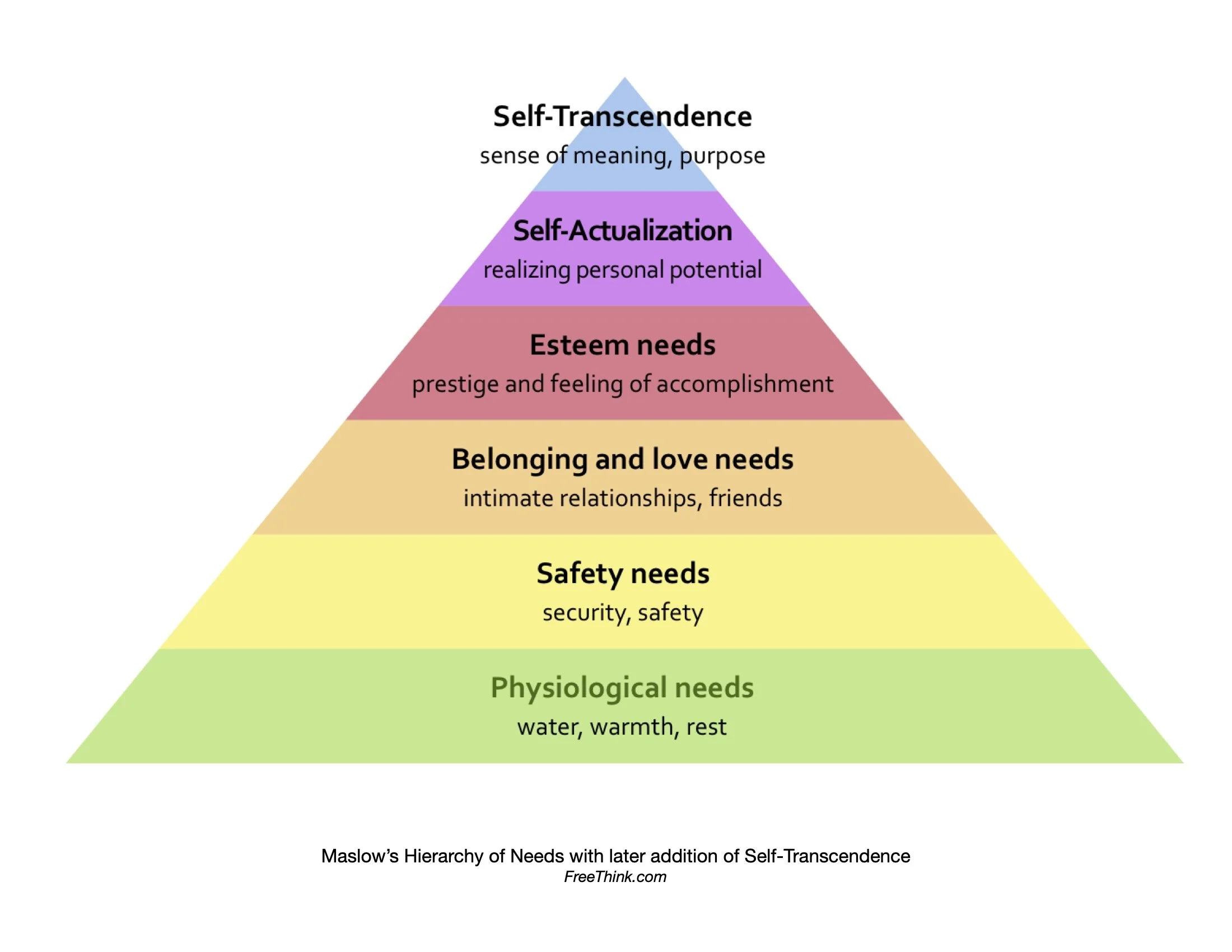

Abraham Maslow even came around to a perspective similar to this idea when late in his life he authored papers in which he put "Self-Transcendence" at the pinnacle of his famous Hierarchy of Needs, in place of Self-Actualization. That is, rather than Self-Actualization being the ultimate human need—life’s highest pursuit—he saw the ultimate goal in life to be investment of one’s life in something that transcends self. To practice such other-centeredness is to love. Self-Actualization is a fine personal motivator for the employment of our innate potential. But it risks manifesting in an avoidant or detached, selfish lifestyle that risks isolation as relationship health is sacrificed on the altar of self-pursuit.

Per Maslow’s ascending needs, our natural tendency is to pursue what we need—at first for survival, then in pursuit of a meaningful life. Without balance, however, self-preservation, self-development, and self-advancement can lead to taking what we need at the expense of others with whom we are in relationship. This poses the risk of selfishness, setting ourselves up against others, defending ourself and our needs against them and their needs. This self-protection is the opposite of protecting the other, which leaves others to fend for themselves, being self-protective against us. In such a scenario, the two parties become caught in an endless cycle of self-defensiveness that tears apart the relationship.

At the other end of the spectrum is love—considerate toward and protective of the wants and needs of others with whom we are in relationship. Such love is demonstrated in the love of a parent toward a child; it is selflessness that sacrifices sleep, the use of time and space, dietary choices, the layout of the home, and many other things for the sake of the child's needs and development. Such other-preferential love is vulnerable because there is no guarantee of reciprocation. Of course, parents and children do not have an egalitarian, interdependent relationship as spouses do; minor children are not expected to sacrificially protect parents in reciprocal ways; that payoff may come with advanced age and inverted dependence. By contrast, in relationships on par, such as marriage, other-centered love is the path to healthy interdependence. Such love is vulnerable because, in protecting the other's needs, we do so without a net; there is no guarantee that the recipient of our other-centered protective yielding will also lovingly yield to and protect our needs and interests. If such reciprocation is not given, there is eventual resentment, rebellion, and detachment.

The ideal in marriage is mutual consideration, mutual sacrificial love, and mutual protection. Through good communication, the feelings, needs, wants and wishes of each partner become understood and are protected by the other. Both are thus alleviated from having to “take” what they need, because what they need is being freely given by their spouse, out of love.

Notice that the arrows in the diagram go only one direction. Instead of each spouse taking at the expense of the other, the ideal is that both give to the other what the other needs for a life that is safe, secure, happy, self-actualized, supported, and relationally satisfying. Not that partners are the complete source of all these things for each other; that would suggest a god-complex. But God does enable us to love more perfectly than we are naturally able (see the fruit of the Spirit in Galatians 5:22-23), regardless of what we receive in return (not excusing neglect or abuse). We can love more deeply, purely, and sacrificially when we draw upon the inexhaustible Source within.

The risk of other-centered love is codependence. Codependents lose their identity and sacrifice their voice amid the life and needs of another. This occurs when there is imbalance; when one is giving from the well of love, and the other is taking from the bottomless pit of self-interest. Eventually, the one over-giving without reciprocation will burn out, resulting in resentment. The kind of love we’re talking about is not codependence, but self-respecting, other-centered interdependence such as promised in the traditional wedding vows. Therein lies the mutual promise to help, comfort, love, serve, and support one another for better or for worse, in wealth and in poverty, in sickness and in health. This interdependence in marriage is designed to reflect the faithfulness of God, who is depicted as betrothed to his people - forever trustworthy, loyal, available, loving and protective.

The box in tension with other-centered love includes authenticity and self-actualization. These are healthy and legitimate pursuits. But, this box can also be imbalanced. Marital oneness requires adjustment. After all, to live however we wish, to make whatever decisions we want to make without consultation or consideration, to say whatever we want to say, however we want to say it, and to do as we please without regard for how it affects others—that is called living alone. Such self-centeredness nearly guarantees detached isolation. By contrast, in marriage, both partners adjust for the sake of the other and are thus changed for the better by altruistic, other-centered love. By living in a way that is caring and considerate of another, we don’t lose ourselves, becoming an appendage of our spouse (codependence); rather, we find ourselves by giving of ourselves (Matthew 16:25). We discover that an interdependent team is stronger and better in myriad ways than living authentically in isolation (Ecclesiastes 4:7-12). In the apostle Paul’s letter to the ancient church of Philippi, he essentially articulates this approach to relationships: “Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility count others more significant than yourselves. Let each of you look not only to his own interests, but also to the interests of others.” (Philippians 2:3,4)

When adjustments are made to one another out of such mutual consideration, there exists a balanced, interdependent relationship. When this does not occur, such as if a partner is inconsiderate, disrespectful, selfish, bullying, or abusive, boundaries must be erected. An extreme example of this would be domestic violence, where other-protective love is wholly absent. In this case, the abused spouse must erect boundaries of self-protection against violence and disrespect, making clear in words and actions what will not be tolerated—even to the point of leaving. Boundaries do not impose a change on someone else, boundaries educate others on what is essential to us. For example, it is not a boundary to impose on someone else the edict, “You have to clean up your language.” Instead, a boundary might state, “I won’t be yelled at and cussed at; I’d be glad to talk through this respectfully.” Boundaries are best stated as positive requests that cast a vision for what is desired, such as, “I’d be glad to talk through this in a mutually respectful way.” This positive request is even more powerful when followed by an affirmation, such as, “I’d be glad to talk through this in a mutually respectful way, like we did yesterday when discussing what to do this weekend.” Or, “I appreciate the way you’re limiting your drinking when we’re out together. And I appreciate your support last Saturday of me being the designated driver. It made me feel safe and protected. Thank you.” Such positive requests with an affirmation keep boundaries from sounding like criticisms, which would likely raise defensiveness. Rather, they trade a criticism for a compliment, which rarely brings defensiveness, unless something else is at play, such as a wounded background or a personality disorder.

Finally, Abraham Maslow’s recognition that self-transcendence is a higher human need than self-actualization in achieving a satisfying life brings the illustration full-circle. Self-transcendence through other-centeredness (love) pursues something higher than the self and thereby gives meaning to life. Examples of this include volunteerism, military service, social work, teaching, organ donation, and missionary service, to name a few. These are examples of giving sacrificially to movements and missions in capacities that yield little status or income. Why would people make such choices? Because selflessness brings richness to life; such choices prove the adage that it is indeed more blessed to give than to receive. Altruism that empties oneself in service to something that transcends oneself paradoxically fulfills oneself.

Marriage is a unique environment in which this ideal of other-centered self-transcendence is pledged—living lives of mutually interdependent loving support of one another.